Change the problem: 18XX token placement

— modellingIt's surprising how often you can translate one problem into another problem, for which there are known solutions and/or algorithms. For example, with Green's theorem you can choose between solving a line integral or a double integral, and select whichever option is simplest to solve. The necessary ingredients are:

- Being aware of the equivalence between two problems; and

- Knowing how to solve (at least) one of these problems.

One example that I found (by accident) was that preserving the connectivity of all placed tokens when upgrading a tile in an 18XX board game is equivalent to solving a maximum flow problem.

While the first problem (preserving token connectivity) can be solved with brute force, there are well-studied algorithms for solving maximum flow problems, such as the Edmonds-Karp algorithm. Re-implementing a well-known algorithm can be easier than implementing something new and, as a bonus, there are often many example problems you can use to test your implementation!

But first, some explanation is required …

Tiles, tracks, and tokens

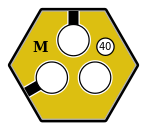

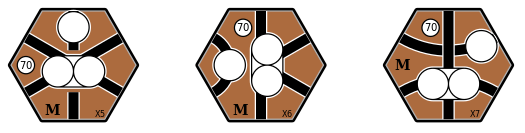

Board games in the 18XX family typically have a hexagonal grid map, which depicts a geographical area that contains cities and terrain such as rivers and mountains. Hexagonal tiles are placed to expand the railway network. Tiles contain track segments (shown here as black lines/arcs), and may also contain revenue centres (such as cities). Revenue centres can have reserved spaces (shown here as white circles) in which tokens may be placed. Tokens are used to represent stations operated by different companies.

For example, Figure 1 shows a yellow tile with three separate revenue centres, each of which can contain one token. The top and lower-left revenue centres are connected to track segments that may link to track segments on neighbouring tiles.

$40.As shown in Figure 2, companies may place tokens in these revenue centres in order to secure routes through these revenue centres, and to prevent other companies from operating routes that pass through these revenue centres.

Upgrading tiles

Tiles of different colours become available as the game progresses, and may be used to upgrade existing tiles.

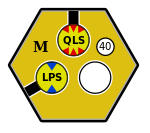

Figure 3 shows five green tiles that could be used to upgrade the yellow tile in Figure 2 (with revenue increased from $40 to $50).

These tiles all include three revenue centres, each of which can contain one token.

Let's consider upgrading the yellow tile in Figure 2 to the X2 tile (the top-right tile in Figure 3).

Note that we need to preserve the existing connectivity of each token.

This means that the QLS token must be connected to the top face of the upgraded tile, and the LPS token must be connected to the lower-left face of the upgraded tile.

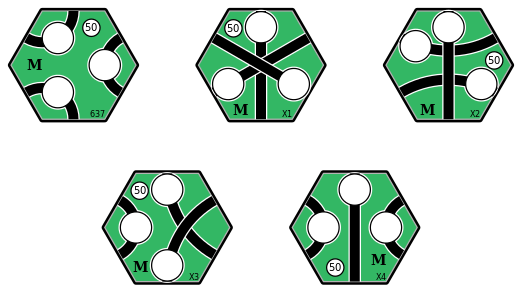

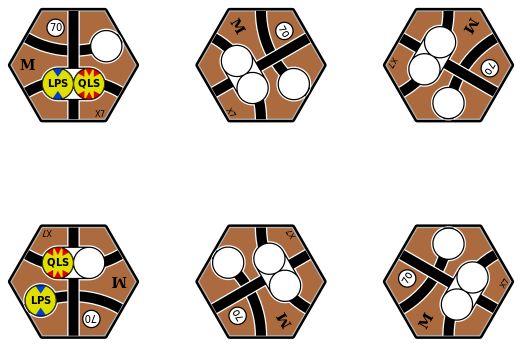

While there are six possible ways that we can orient the X2 tile, Figure 4 shows that only four of those orientations can preserve the token connectivity.

X2 tile, with tokens placed only when it is possible to preserve their connectivity.These green tiles can, in turn, be upgrade to brown tiles.

Figure 5 shows three brown tiles that could be used to upgrade the green tiles in Figure 4 (with revenue increased from $50 to $70).

Let's consider upgrading the top-left green tile in Figure 4 to the X7 tile (the right tile in Figure 5).

Note that each token is now connected to two tile faces — the QLS token to the top and bottom faces, and the LPS token to the lower-left and lower-right faces — and we need to preserve this connectivity.

Again, there are six possible ways that we can orient the X7 tile, but

Figure 6 shows that only two of those orientations can preserve the token connectivity.

X7 tile, with tokens placed only when it is possible to preserve their connectivity.Framing this as a maximum flow problem

We are searching for an allocation of tokens to revenue centres that preserves the existing connections between tokens and tile faces. As we saw in Figure 4, a valid allocation may add additional connections between tokens and tile faces.

Maximum flow problems involve finding a flow from a source node to a sink node that obtains the maximum possible flow rate, in directed graphs where each edge has a maximum capacity. Consider each token as a flow source — that is, each token creates a demand that must be met — and each revenue centre as a pipe with some maximum capacity (the number of token spaces). Connect each token to only those revenue centres that preserve the token's connections. The maximum possible flow rate in this network is the sum of token flows — the total demand — and if such a flow is possible, then there is a valid allocation of tokens to revenue centres!

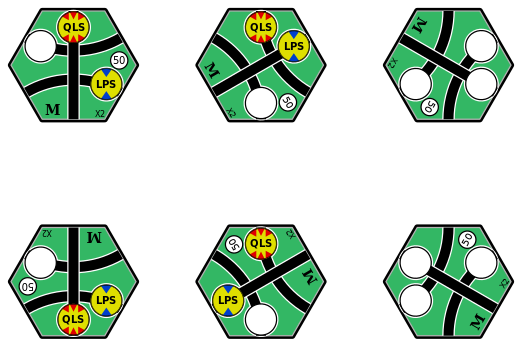

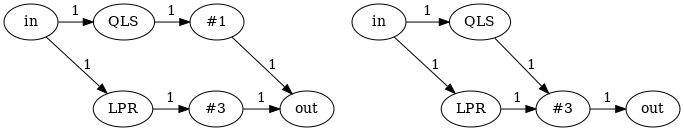

Consider the yellow tile with placed tokens, and the two orientations of the green X2 tile, shown in Figure 7.

Does either orientation of the X2 tile allow us to preserve the connectivity of the tokens placed on the yellow tile?

X2 tile, which numbered revenue centres.For the first orientation, only revenue centre #1 preserves the QLS connectivity, and only revenue centre #3 preserves the LPR connectivity.

For the second orientation, only revenue centre #3 preserves the connectivity of QPS and LPR.

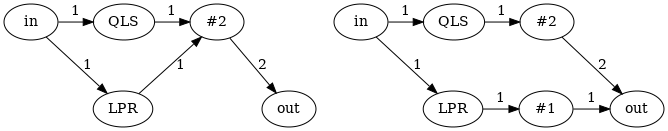

The flow networks for these two orientations of the X2 tile are shown in Figure 8.

It is clear that the first orientation can preserve the token connectivity, and that the second orientation cannot preserve the token connectivity because revenue centre #3 can only hold one token.

X2 tile.An overview of the algorithm

We can divide the problem of placing tokens on the new tile into the following steps:

-

For each token on the original tile:

a) Identify the tile faces to which it is connected; and

b) Identify each revenue centre on the new tile that has these connections.

-

Construct a flow network that contains:

- A node for each token on the original tile;

- A node for each revenue centre on the new tile;

- A connection from the source node to each token node, with capacity 1.

- Connections from each token to the revenue centres identified in step 1b, with capacity 1; and

- A connection from each revenue centre node to the sink node, with capacity equal to the number of token spaces in that revenue centre.

-

Calculate the maximum flow using any one of the many published algorithms.

If the flow is equal to the number of tokens, the tokens can be placed on the new tile. Each non-zero flow from a token node to a revenue centre node indicates that the token should be placed in the corresponding revenue centre.

A slightly more complicated example

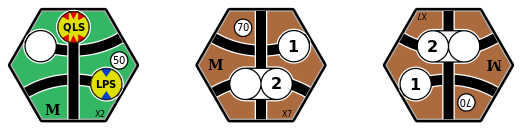

Consider the green X2 tile with placed tokens, and the two orientations of the brown X7 tile, shown in Figure 9. Does either orientation of the X7 tile allow us to preserve the connectivity of the tokens placed on the X2 tile?

X2 tile with placed tokens, and two orientations of the brown X7 tile, which numbered revenue centres.Using the same approach as before, we can construct flow networks for each orientation of the X7 tile.

These flow networks are shown in Figure 10.

We can see that both orientations can preserve the token connectivity.

X7 tile.Final remarks

I have only shown simple examples where for each token, only one revenue centre is able to preserve its connectivity. When multiple revenue centres can preserve a token's connectivity, the token's node will have multiple outflow edges. If there are multiple tokens that have more than one outflow edge, the flow network can be sufficiently complex that is hard to determine whether a solution exists from a visual inspection of the network. These are the situations where being able to apply a well-known algorithm provides the greatest advantage to implementing your own solution from scratch.

All of the tile figures were generated using my navig18xx Rust library, which provides a graphical user interface for constructing 18xx maps and identifying optimal train routes. It's roughly 28,000 lines of Rust code, and probably the single biggest piece of code I've written to date. The size of the code base was one reason I wanted to find an off-the-shelf solution for this problem.